Rock Art3 !Churinga

As I have already noted, Graham Walsh’s national survey of rock art in 1988 concluded that the rock art styles south of Townsville are unique in their ‘design’ – a distinctive regional style. For him and for many others they are reminiscent of ‘shields’, and in particular the large and ceremonial ‘rainforest shields’ that were made north of the Townsville region. The large trees from which these shields were made do not grow in the Dry Tropics environment surrounding Townsville, and there is therefore the implication that the ‘shields’, as illustrated, would have been bartered and therefore provide evidence of tribal interaction and trade.

But we don’t need these to be shields to know that there was a well-established trade network, especially along the coast as described by Charles Price in 1885:

The writer, who has for, above 16 years studied the dialects of the “aboriginals” of the tribe the “Coonambella” or propose speaking the dialect spoken by those savages who form the tribe occupying the country between the Rivers Ross + Black and the plains “Caria” as far inland as the coast chain of Mountains “Baringa” the immediate tribe adjoining being “Wombela” North, and Woodstock “South” who are friendly generally speaking and occasionally make visits to each other, especially the Northern or “Wombela” tribe who are great manufacturers of various weapons of warfare “ornamented neck beads” Fancy Baskets, “Spears” Swords, Fishing Nets, and amongst whom the old people belonging to the Coonambella tribe have great welcome, generally ending their days amongst them.

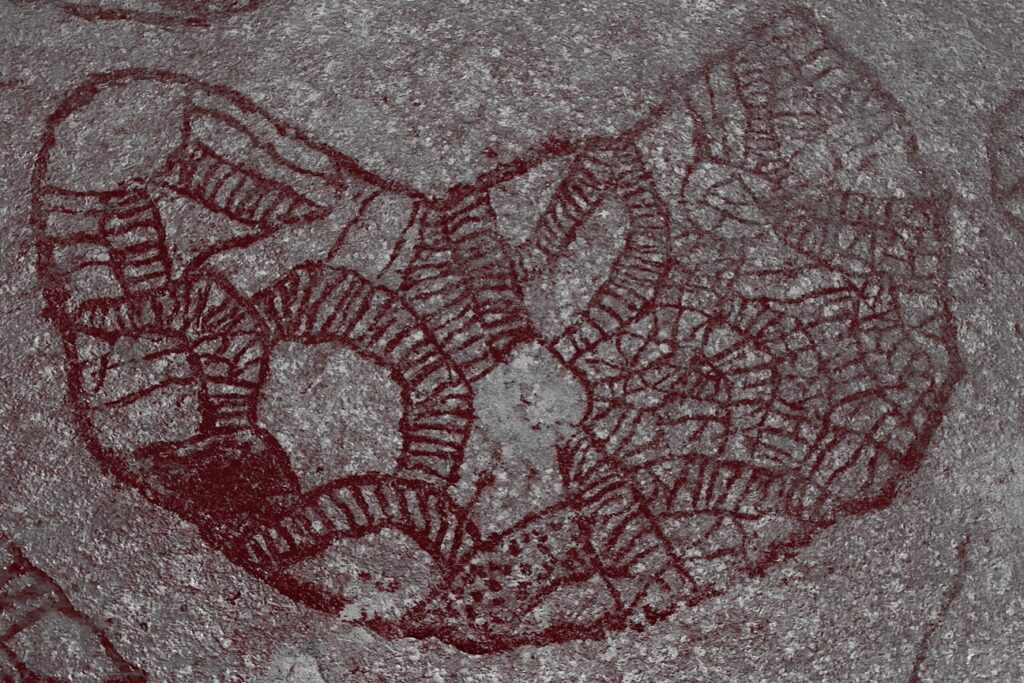

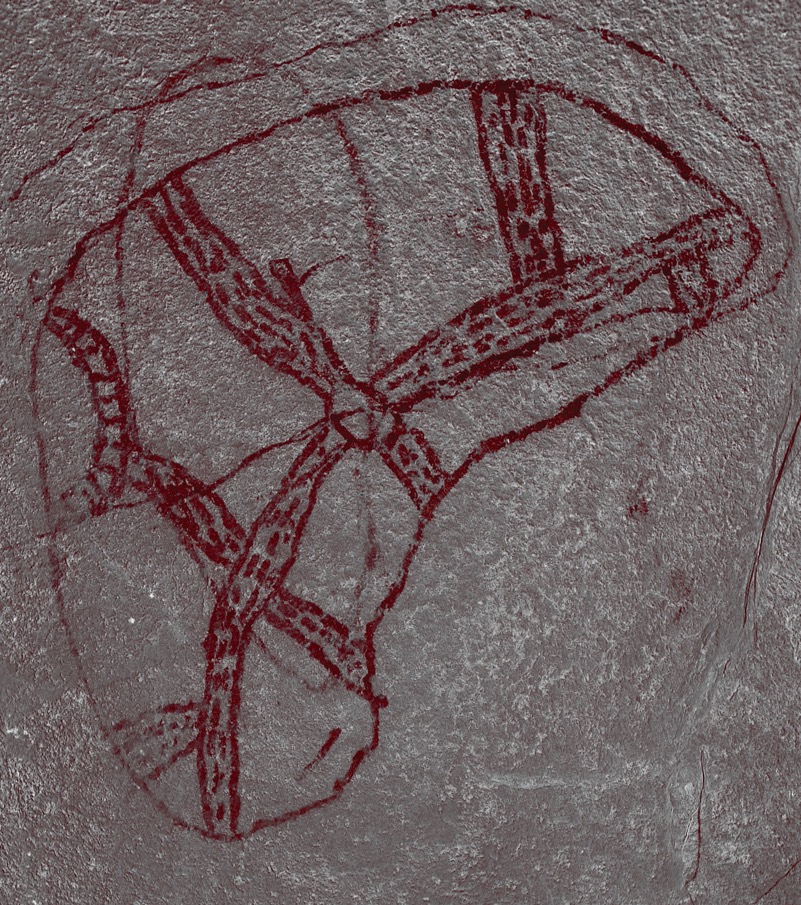

As I have also illustrated there is little evidence that the painted designs of rainforest shields have informed the designs of the rock art south of Townsville, particularly because the latter are not symmetrical. Examine closely the following examples.

The designs are all enclosed by distorted ovals and what could be interpreted as the boss of a shield. The central circle is certainly important. It occurs in many of the paintings, and I prefer to interpret it as the ‘centre’, perhaps a meeting place, perhaps a water hole, but of a significance that makes the other elements link to it repeatedly. And these ‘other elements’ can be very complicated.

For instance, in #1 there are the usual four major connections, but connected to these we can see a further 12 entirely unsymmetrical elements and particular care has been taken to delineate their shape and note also that one of these has been filled with ‘dots’ rather than dashes. This is language. It is telling us something.

In #2 we see something similar with the usual four major connections but also with ancillary elements, one of which ends on the cusp of a semicircular design attached to the outer boundary. A much more complicated rendition of this design can be seen in #3.

The real meaning of these designs will never be known, but I suggest that there is a ‘connectedness’ in these images, from which the repeated elements create a ‘language’ which suggests that some sort of story is being told. But how can we attempt to interpret them?

One avenue is to explore ethnographic records from elsewhere and in Central Australia there are some such records which illustrate compelling similarities to the Townsville images. These were recorded at the close of the 19th century by Baldwin Spencer and Frank Gillen, who made pioneering accounts over a twenty-year period of the Arunta (Arrernte) people. Whilst not without controversy, their work enabled detailed recording of culture and ceremony that elsewhere was entirely lost.

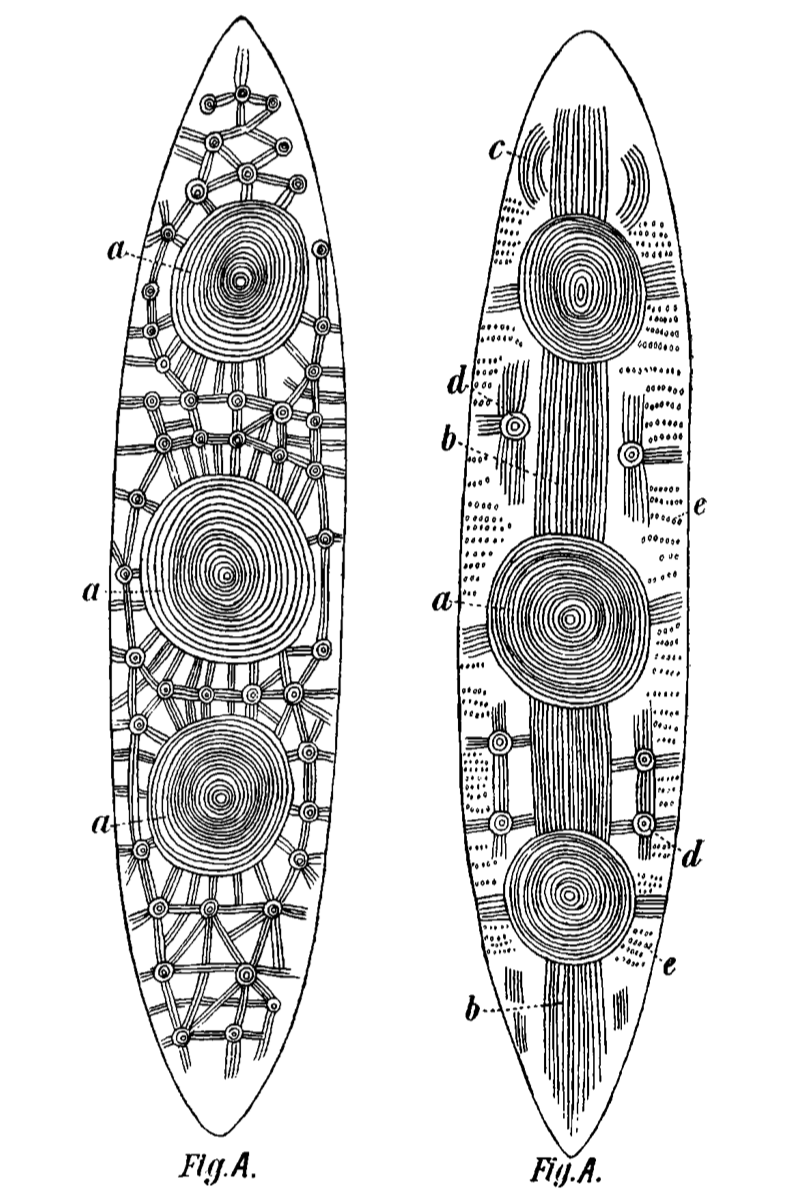

Fig. A represents the designs on a Churinga, a wooden object some 39 cms long and carved on both sides. The Churinga is the dwelling place of the spirit of the Alcheringa (Dreaming) ancestors1 and as such is an object of potent magic.

I am not suggesting that the Townsville images are ‘churingas’, but the fact that the images use simple design devices, and that they are repeated and repeatedly connected suggests a similar kind of language making. This object is carved on both sides and is described by Spencer and Gillen as follows:

Figure A. represents the Churinga nanja2of a dead man of the frog totem. On either side of the Churinga, are three large series of concentric circles (a), which represent three large and celebrated gum-trees which grow by the side of the Hugh River at Imanda, the centre of the particular group of the frog totem to which the owner of the totem belonged; the straight lines (b) passing out from them on one side of the Churinga represent their large roots, and the two series of curved lines at one end (c) their smaller roots. These trees are intimately associated with the frog totem, as out of them frogs are supposed to come, which is doubtless an allusion to the fact that in the cavities of old gum-trees one species of frog is often found, and can be always heard croaking before the advent of rain. The smaller series of concentric circles on the same side of the Churinga (d) represent smaller gum-trees, the lines attached to them being their roots, and the dotted lines (e) along the edge are the tracks of the frogs as they hop about in the sand of the river bed. On the opposite side of the Churinga the large series of double concentric circles represent small frogs which have come out of the trees, and the lines connecting them are their limbs.3

It is impossible to understand the context of the churinga and the text above without an understanding of Aboriginal spiritual beliefs and ceremony. In the beginning was the Dreamtime (Alcheringa) when the ancestral people came into existence:

these ancestral people…started to walk across the country, lizard people along one track, kangaroo people along another, frog people along another and so on, right through the various totem groups. Every one of these ancestors possessed, and often carried with him, or her, a sacred Churinga, with which the spirit part of the individual was supposed to be intimately associated. As they wandered over the country, they made all the natural features- mountains, valleys and plains, creeks, clay pans, water-holes and gorges -that are now familiar to the natives. At certain places they halted to perform ceremonies, and there, certain members of the different parties died, or, as the natives say, went down into the ground; that is, their bodies did, but their spirit parts remained above in company with the Churinga and stayed behind when the party moved on, remaining in some rock or tree that was ever afterwards sacred to them and was called that individual’s Perta knanja or Rola knanja, that is, his totemic rock or tree. It very often arose to mark the spot where the ancestor died.4

In other words, the churinga illustrates the story of a particular totem (frog) which is associated with a striking or unusual physical feature, in this case three large gum-trees, which are consequently sacred sites. As there are many such totems then the Aboriginal:

moves not in a landscape, but in in a humanised realm saturated with significations. Here ‘something happened’; there ‘something portends5

And central to these beliefs is that all ancestors are ‘reincarnated’ from the spirits that were left at the significant totem site.

When a woman conceives it simply means that one of these spirits has gone inside her, and, knowing where she first became aware that she was pregnant, the child, when born, is regarded as the reincarnation of one of the spirit ancestors associated with that spot, and therefore it belongs to that particular totemic group6

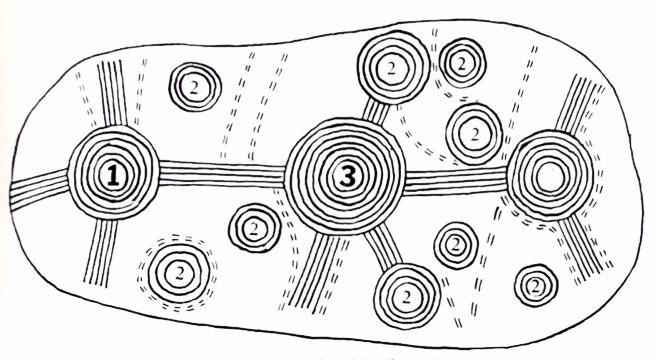

This example of a stone churinga illustrates the grasshopper totem from the Ngalia tribe of Central Australia. The symbols are explained on the churinga and referred to while the story is told.

At a place called Ngapatjimbi (1) there were a number of grasshoppers. They came out of the ground, and flew up, and coming down they went into the ground again. The grasshoppers multiplied, and after the next rain they came out of the places marked (2). They flew up and came down as men. These men went to Wantangara (3), and going into a cave, turned into churingas

On this particular churinga the bands of parallel lines linking circles represent the paths the grasshoppers made by breaking down leaves. Pairs of lines represent their tracks.7

In some ways these churinga and rock art paintings might be considered to be ‘storyboards’. The language is simple, with similar designs often repeated, circular, semi-circular, spiral, curved and straight lines together often with dots. The simplicity belies the intention of reinforcing cultural continuity and cultural memory so that the stories are safeguarded and passed on to future generations.

1 Native Tribes of Central Australia Spencer and Gillen 1899 p.13

2 As we have said, the exact spot at which a Churinga was deposited was always marked by some natural object, such as a tree or rock, and in this the spirit is supposed to especially take up its abode, and it is called the spirit’s Nanja. Native Tribes of Central Australia p.123

3 Native Tribes of Central Australia p.145

4 Wanderings in Wild Australia Spencer and Gillen 1928 p.

5 White Man got No Dreaming WEH Stanner 1979 p.13

6 Northern Tribes of Central Australia Spencer and Gillen 1904 p.150

7 Old and New Australian Aboriginal Art Roman Black Angus and Robertson 1964 p. 64