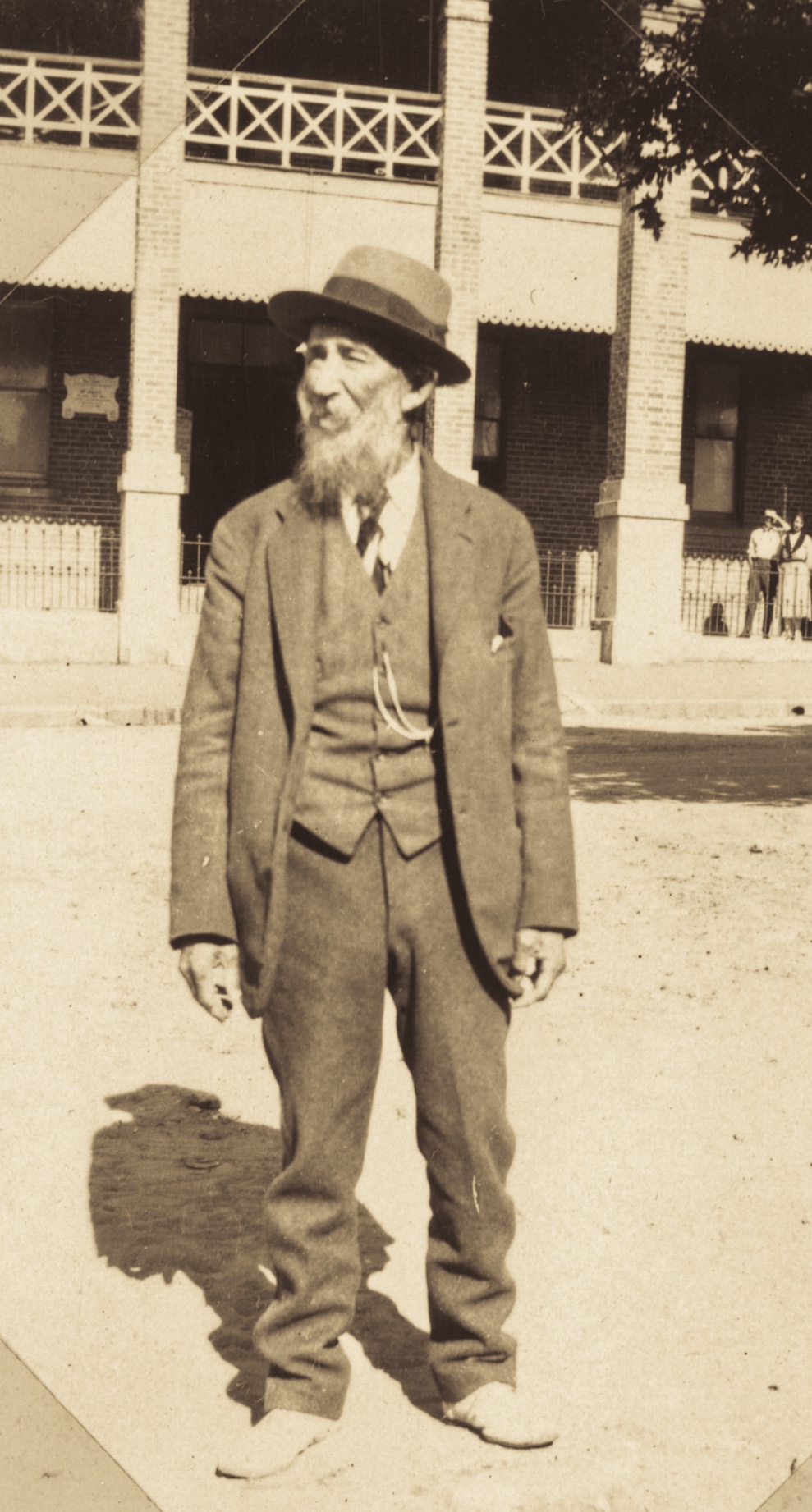

Charles Price 1842-1926

Towards the close of the 19th century colonial expansion in North Queensland was both swift and enterprising, and Townsville became the ‘entrepot for a region vast in extent, all but unique in its diversity of industrial needs and productive potentialities’.

There is an audible whirr in the activity of its prosperity – the hum of busy money-making is in the very air. The population has doubled itself within two years, and the population is a purposeful population.1

The visiting British journalist Archibald Forbes made these observations in 1883, describing the world in which Charles Price lived and worked. Born in Oswestry, Shropshire in 1842 he arrived in Brisbane in 1870 on the Black Ball Line immigrant ship Young Australia, and then travelled north to Townsville where he married Ellen Shekelton in 1873.

Little is known of Price’s early life, but he became a businessman, buying several properties in town and establishing a drapery business, Charles Price & Coy. which moved premises several times in Denham Street before moving to Flinders Street in 1878. The land purchases and changes of address may have been because:

Townsville is one of the most brilliant examples of the extraordinary rise in the value of land, which so often takes place in new countries. Ten years ago, anyone might have bought an allotment for fifty or perhaps thirty pounds in the best situation; three or four years ago, the same would have fetched three or four hundred; while now, good frontages in Flinders Street have been sold for two hundred pounds a foot.2

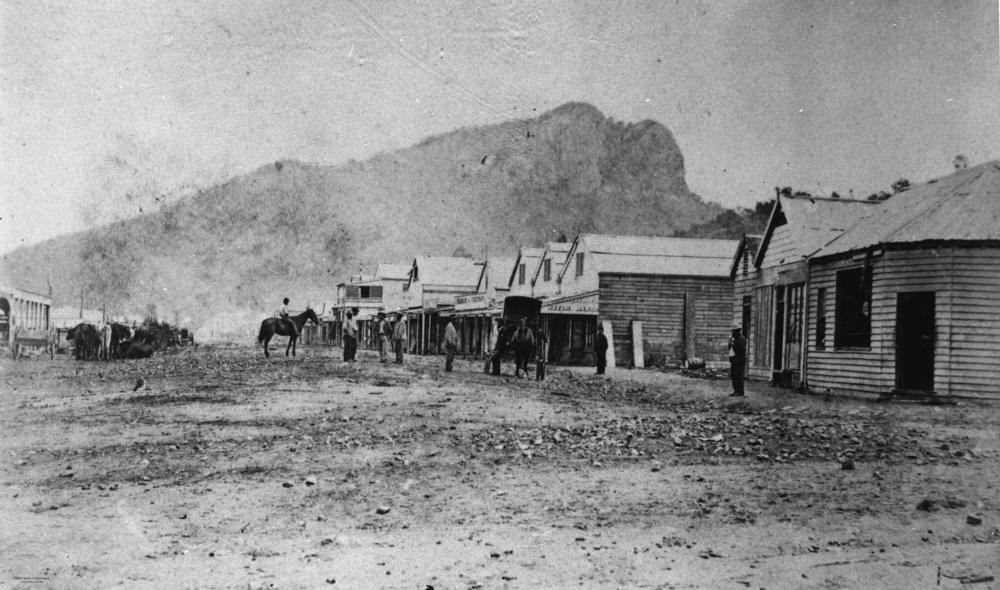

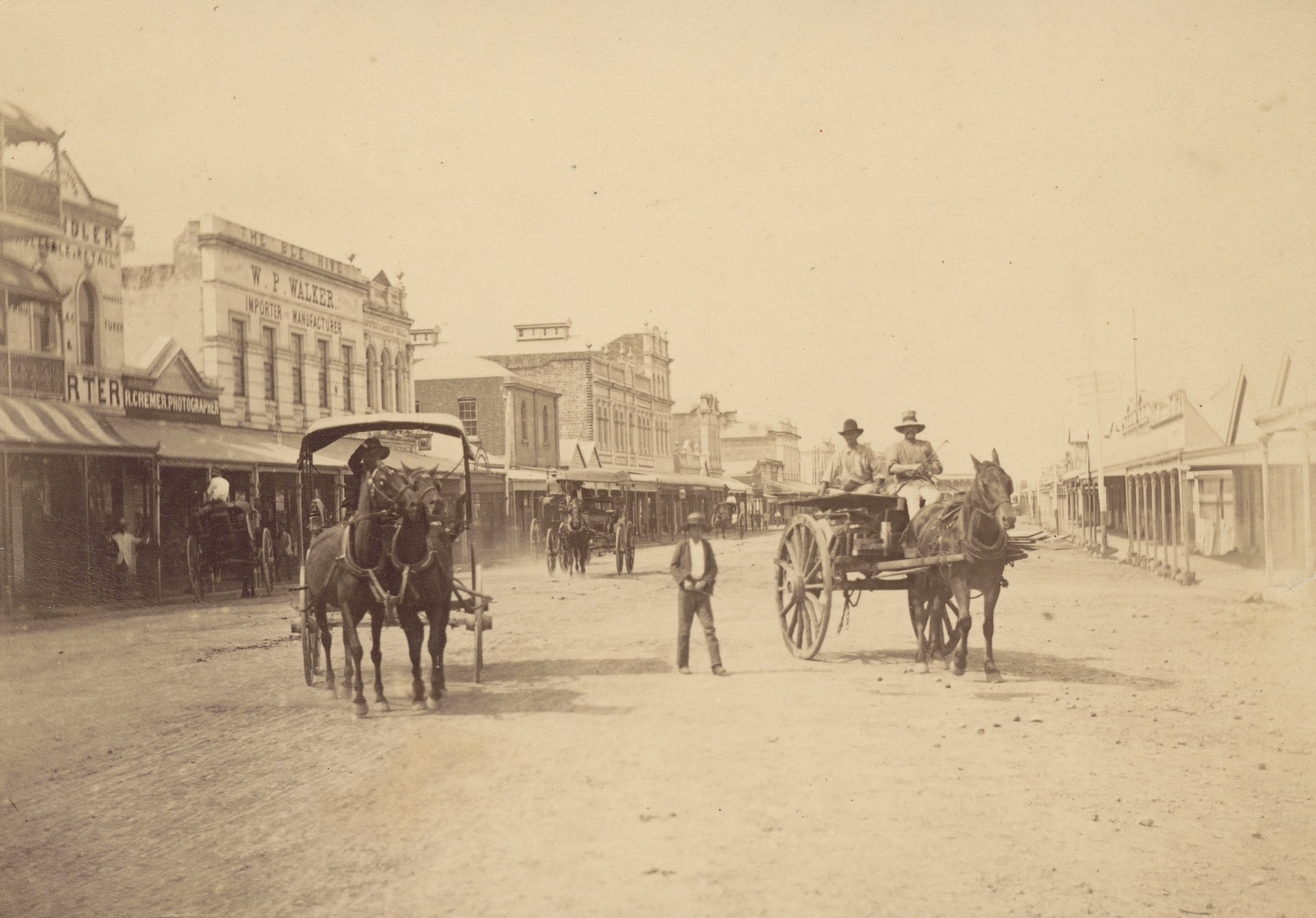

Flinders Street when Price arrived in Townsville c1873 above and c1888 below

On the 21st of March 1876 he was aboard the SS Banshee headed north for the Endeavour River and the newly established settlement of Cooktown. Like many others he was almost certainly taking advantage of the newly announced Hodgkinson gold rush and planning to establish a business there, but whatever the reason for his journey it ended with the total loss of the ship, wrecked on rocks at the far north east of Hinchinbrook Island, now memorialised as Banshee Bay. The dramatic and gruesome events were recorded by Price and published in the Townsville Times, as set out below. In all there were 20 fatalities and 33 survivors from this stormy shipwreck.

At the end of 1878 Price was also burdened with a fire which destroyed his old premises on Denham Street which were not insured, and the buildings value of £300 was born by Price and Coy. But a year later his business was advertised as Charles Price and Coy., Civil, Naval and Military Tailors and Outfitters, a name which perhaps reflects the growing prosperity of Townsville. And in 1879 Mr and Mrs Price had a son named Stanley Shekelton Hardgrave Thankful Price.

Throughout these trials and tribulations, Price, by his own testimony had studied and recorded the dialects of the local Aboriginal tribe since his arrival in the town. This was a very unusual pursuit at a time when the Aboriginal population were excluded from the ‘audible whirr’ of prosperity and were in fact ‘fringe dwellers’ whose traditional way of life had been entirely destroyed. He was acutely aware of the rapid loss of Aboriginal culture as he makes clear in the preface to the handwritten book that followed:

The only good chance that ever occurred, giving a proper insight into the Wild aboriginal life was lost some time ago when James Morrel, a wrecked Sailor Boy was found near a station between Townsville and Bowen some years ago, after having lived amongst the Blacks for 15 years. There was a small pamphlet (only) printed but it did not treat of the native language or in any way give much idea of the real life

He also indicated the manner in which he recorded the words and phrases and at the same time reveals a ‘bookishness’ in his personality, which may have reduced his ability to acquire a fuller knowledge of the vernacular:

There are several men who having lived several years partly in the company of the “Blacks” who can say a good many words, idioms etc who have had by their positions “Wild Fowl Sporting” better chances for acquiring proficiency in the colloquial than myself because they have had the “native” constantly in their company, which I have not been able to do. As their interest lay in the bush and mine in the town my only chance therefore has been to snatch a chance at every time when seeing a native about my private house, and in all cases I always took care to memo every new word that came to my ears, and it is by this alone that I can safely say that my collection is the only ‘Written Collection” of the native dialect of “Coonambella” and probably the only written records of the language used by the natives of Northern Queensland.

Price wrote these words in August 1885 as a part of a ‘note’ to the handwritten exercise book in which he copied out some 95 pages of words and phrases, which he had collected over 16 years. The exact circumstances of the book’s compilation are not clear but at the end of February 1886 the Queensland Times reported from Townsville that:

Mr Charles Price, an old resident, has prepared an extensive vocabulary of the language of the Aboriginals in the neighbourhood of Townsville. The work, which had occupied many years, had been sent to Brisbane, to the Commissioners for the Indian and Colonial Exhibition, to be forwarded to London. Mr Price leaves here, for London in May.3

The Indian and Colonial Exhibition was organised by the Prince of Wales as an ‘Imperial object lesson’, in England’s colonial holdings and its power and grandeur.4 It was held in South Kensington between May and November 1886 and by its close had welcomed 5.5 million visitors. There was considerable interest in this Imperial jamboree and the Queenslander reported from Townsville at the end of March as follows:

The Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886 would have looked very similar to this portrayal of the 1851 Exhibition published by Dickinson Brothers

Townsville will be well represented at the Indian and Colonial Exhibition. In addition to Dr. Ahearne, Mr. Henry Aplin, and others, who are at present in London, the Dacca will take on her next voyage the Hon. William Aplin, Messrs. W. Harm (of Maryvale), W. Kirk, and others not so well known. Mr. Robert Philp, M.L.A., would also have journeyed to London at the end of the month but for his Parliamentary duties.

Townsville will contribute very little to the Exhibition. Save for a pamphlet upon the resources of the district, and the condition and prosperity of the North generally, and a manuscript work on the language of the blacks, old Townsville citizens, now resident in London, will look in vain for something to remind them of the place.5

This cursory mention of the manuscript perhaps reflects the general disregard for Aboriginal culture, and Price himself is overlooked. A description of the book on display in London also suggests only a passing interest.

At the Colonial and Indian Exhibition attached by a chain to the desk – reminding one of similar practices in churches in olden days with regard to a bible – is a book in manuscript form prepared by Charles Price of Townsville in which is a vocabulary and other information connected with the native dialect of Coonambella. Mr Price is an evidently intelligent exponent of the language; a brief study of his work convinced me of his laborious application although I fear I should require more than one lesson to place me on a conversational terms with the Coonambellans.6

The book was subsequently presented to the Royal Commonwealth Society by the Executive Commissioners of Queensland at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in 1887, and it now resides in their library at Cambridge University. At the same time Price is credited with the donation of 69 Oceania artefacts to the British Museum. These may have been collected originally to compliment his book display and it may be that their provenance is hinted at in this brief report in the Queensland Times from their Townsville correspondent:

Messrs. Aplin, Brown, and Co.’s schooner Currambene left, last evening, under charter to the Government, for Port Moresby, for the purpose of bringing a collection of curios for the Indian and Colonial Exhibition, to be conveyed to London by the B. I. S.N. Company’s steam-ship Dacca. If she has not time to return here by the 27th of March, the Currambene will catch the Dacca at Thursday Island, and tranship her cargo there.7

This collection consisted of 58 artefacts from Melanesia, mainly Papua New Guinea, and 11 from Australia.8 These latter consist of boomerangs, clubs, a spear, and a knife made of recycled iron with a gum handle covered in fur and acquired ‘from Cleveland Bay North Queensland’.9

Of Price’s personal life on his return from London very little is known. He continued as a Draper until at least 1897 but it is clear from the annual Electoral Rolls for Townsville that his business interests had not made him a wealthy man. In 1900 he was appointed Sheriff’s Bailiff in Townsville, a post he held for only 9 months.10 After that and until his wife’s death in 1911 they lived in Sixth Avenue South Townsville, and Price’s occupation is given as ‘debt collector’. Thereafter, he moved lodging frequently so that for instance in 1916 his entry in the Electoral Roll is given as ‘c/o Watkins, back Crown Hotel, McIlwraith St. South Townsville debt collector’.

In 1913, when Price was 71 years old, Townsville chose to celebrate its ‘jubilee settlement’ and a published list of prominent ‘pioneer citizens’ includes only the briefest description: ‘Mr Charles Price is a very old resident and is expert in aboriginal dialects and Esperanto’.11

By 1922 the Electoral Rolls record his occupation as ‘clerk’, which remains unchanged until his death in January 1926 at the age of 83:

One of the very oldest residents of Townsville, in the person of Mr Charles Price passed away last week, aged 84. Mr Price commenced business as a draper in Flinders Street, Townsville, some 50 years ago, and his store did a fine business, especially when a schooner load of kanakas, who had just been paid off, and were being repatriated to their Island, anchored in the Bay. Mr Price retired from active business some 30 years ago but has been a resident of Townsville all the time. He was an exceedingly well-informed man, and his assistance was often sought on various matters. His evenness of temper and good humour made him a great favourite with those who knew him, and the report of his demise will be received with widespread regret.12

He was laid to rest in Belgian Gardens Cemetery on the 8th of January 1926.

1 Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 – 1912), Saturday 16 June 1883, page 1109

2 The Never Never Land: A Ride in North Queensland

A W Stirling 1884 p. 71

3 The Brisbane Courier 24th February 1886

4 Briefel, Aviva. “On the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 10th August 2021

5 Queenslander 20th March 1886 p. 469

6 Townville Herald 4th August 1886 p. 5

7 Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser 23rd February 1886 p. 2

8 www.british museum.or/collection/term/BIOG127350 (accessed 15th August 2021)

9 British Museum Oc1886, 1015,1

10 Brisbane Courier Fri 6 July p. 4 and North Queensland Register Mon 15 April 1901 p18

11 Queenslander 13th September 1913 p. 29

12 Townsville Daily Bulletin 12th January 1926 p. 4

The University of Cambridge Digital Library have made Charles Price’s Notebook available in its entirety:

A full report on the Wreck of the Steamer Banshee was published in The Capricornian on the 8th April 1876, p. 237, which included this first hand account from Charles Price:

The Townsville Times furnishes the following account by a passenger:— Charles Price states that after the vessel struck he laid hold of the boom, and then the funnel came down knocking him between decks ; then jumped up on the side rail and caught hold of one of the spars; managed to get on one of the rocks ; then looked round and saw the stewardess and Pat Ryan hand-in-hand ; they jumped into the water and separated; then saw the engineer and Miss. Antoine clinging to a spar, she on the top and he underneath; she had hold of one of his legs with one arm and clung to the spar with the other; Price then went out and endeavoured to save the woman, and succeeded in catching her by the hair; she said — ‘For God’s sake help me, help me!’ Price said ‘Let go your hands’; the sea then dashed up and the woman was washed away; Price was then driven on to the rocks with the woman’s hair in his hand; he next saw the Captain holding on to a rock, and got hold of his hand and pulled him up ; the Captain then cried — ‘For God’s sake, save her,’ meaning the stewardess, who was clinging to a piece of wreck between the ship and the rocks; Price was about to go to her assistance, but a sea came up and took her under the ship; she came back again and caught a rope which was hanging from the wreck; Price and one of the firemen caught hold of her and dragged her on to the rocks; the captain and Mr. Burstall then carried her to a safe place in the shelter of a

cliff – then looked round and saw a man clinging to a rock – he made towards him, but the man, before he reached him, was washed right underneath the ship, just when she was bumping on the rock, and cut the poor fellow in two pieces; saw the lower part of the body wash up again ; while attempting to save Mrs. Antoine, saw Mrs. Welsh looking through the window of the saloon, one of her children hanging on to her neck: the saloon was immediately smashed in, and Price saw no more of her; he then saw the man that was looking after the horses for Welsh lying on the deck with one of the horses lying on his head smothering him; the sea shortly afterwards washed both horse and man away; next saw the cook come out of the after part of the ship and step on the rock; he stated that he had been jammed by the machinery and could not get out before; the survivors came ashore, and when counted numbered 33; six men started to cross the island with the hope of attracting attention from Dungeness; they had half a pumpkin as provisions, an old revolver, and a red blanket to be used a signal: the others next morning visited the wreck, and found the body of Mrs. Welsh on the rocks frightfully mutilated, having nothing on her but her boots and rings; they also found the body of another woman, Mrs. Day, on the beach, but so much decomposed that she had to be buried where she lay; the body of Mrs. Welsh was buried on the rocks.